- Mega Menu

-

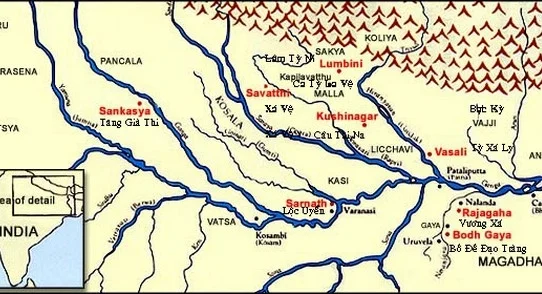

Bản đồ

Lãnh thổ - bộ tộc

Quốc gia thời Phật +Vương quốc Kosala +

Vương quốc Magadha +

Sakya +

Koliya (Câu-lợi) +

Nước Kasi +

Nước Bạt-kỳ (Vajji) +

Nước Avantī +

Xứ Kurū +

Cộng hoà Malla +

Vương quốc Vatsa +

Nước Ālavī +

Nước Pañcāla +

Tích Lan (Lanka - Sri Lanka)

- Cuộc đời Đức Phật

- Hình ảnh

Thông tin từ Wiki.Tamhoc.Org

Hiện 1 số chức năng vẫn đang được xây dựng

Giới thiệu về Wiki Tâm Học .org

- 01/18/2026 08:51:22- 3771 Lượt xem

Trung A Hàm 167. Kinh A-nan Thuyết

- 01/18/2026 08:51:22- 1012 Lượt xem

Tóm tắt kinh Hạnh Phúc (Mangala Sutta, Sb 2.4, Khp 5)

- 01/18/2026 08:51:22- 992 Lượt xem

MN 26: Ariya Pariyesanā Suttaṃ

- 01/18/2026 08:51:22- 771 Lượt xem

Cuộc đời Đức Phật Thích Ca TC007A01 : C - Siddhattha học văn

- 01/18/2026 08:51:22- 770 Lượt xem

All caught up!There are no system errors!Choose Language

Popular Languages

Others

Sách liên quan

Nikaya Tâm HọcTrang chuyên về Cuộc đời Đức Phật

Nikaya Tâm HọcTrang chuyên về Cuộc đời Đức Phật- Activity

-

Chat

8

- Recover Password

- My Account

-

Settings

New

-

Messages

512

- Logs

Nikaya Tâm họcVP People ManagerLayout Options

-

Fixed HeaderMakes the header top fixed, always visible!

-

Fixed SidebarMakes the sidebar left fixed, always visible!

-

Fixed FooterMakes the app footer bottom fixed, always visible!

-

Chế độ xemChế độ xem toàn màn hình

-

Kiểu hiển thị bài viếtBài viết sẽ được sắp xếp dưới dạng

-

Số lượng bài viếtSố bài viết được phân trong 1 trang

Header Options-

Choose Color Scheme

Sidebar Options-

Choose Color Scheme

Main Content Options-

Page Section Tabs

-

Light Color Schemes

- Menu

- Dashboards

- Đức Phật Gotama

- Kinh Tạng Nikaya

- Kinh tạng Nikaya

- Kinh trung bộ

- Kinh trường bộ

- Kinh Tương Ưng Bộ

- Kinh Tăng chi Bộ

-

Kinh Tiểu bộ

- Kinh Tiểu bộ

- Kinh Tiểu tụng

- Kinh Pháp cú

- Kinh Phật thuyết như vậy

- Kinh Phật tự thuyết

- Chuyện thiên cung và ngã quỷ

- Kinh tập

- Trưởng lão tăng kệ

- Trưởng lão ni kệ

- Tiền thân Đức Phật Gotama

- Nghĩa Thích, Niddesa

- Phân Tích Đạo (Vô Ngại Giải Đạo)

- Thánh Nhân Ký Sự (Thí Dụ)

- Phật Sử, Buddhavamsa

- Hạnh Tạng, Cariya Pitaka

- Hướng Dẫn Chú Giải Tam Tạng

- Phần Tìm Hiểu Tam Tạng (Petakopadesa)

- Mi-lin-đa Vấn Đạo (Milindapanha)

- Checkout

- Phần nghiên cứu

- Trung A Hàm

- Trường A Hàm

- Tăng Nhất A Hàm

- Tạp A Hàm

- Nghiên cứu

-

Kinh A Hàm

Đối chiếu và so sánh

Luật tạng

- Thời Phật tại thế

- Nhân và phi nhân

- Thư viện

- Tham khảo

ĐPS T6B.003 EPILOGUEOn Saturday, the thirteenth waxing day of the first Wazo, 1331 Myanmar Era, the 2513th year of the Sǎsana, the month when the Alexandrian laurel Calaphyllum blooms forth in the forest and the traditional festival of admitting new entrants into the Order is being held throughout the land, at eleven a.m.Tìm kiếm nhanh - Cuộc đời Đức Phật

Mốc I : Hoàn cảnh trước khi Phật ra đời

Mốc I : Hoàn cảnh trước khi Phật ra đời

Mốc II : Sự kiện Phật đản sanh

Mốc II : Sự kiện Phật đản sanh

Mốc III: Giai đoạn tuổi thơ của Bồ tát Tất Đạt Đa

Mốc III: Giai đoạn tuổi thơ của Bồ tát Tất Đạt Đa

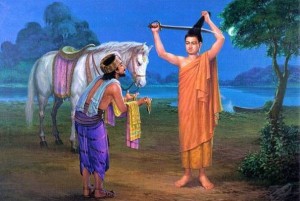

Mốc IV : Giai đoạn trưởng thành - xuất gia

Mốc IV : Giai đoạn trưởng thành - xuất gia

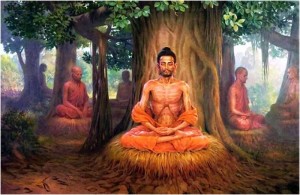

Mốc V : Tầm đạo

Mốc V : Tầm đạo

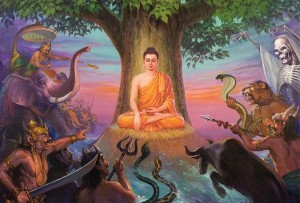

Mốc VI : Thành đạo

Mốc VI : Thành đạo

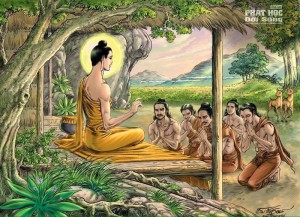

Mốc VII: Những vị đệ tử đầu tiên

Mốc VII: Những vị đệ tử đầu tiên

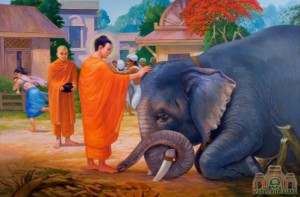

Mốc VIII : Tăng đoàn lớn mạnh

Mốc VIII : Tăng đoàn lớn mạnh

Mốc IX: Mười ba năm cuối cuộc đời Đức Phật

Mốc IX: Mười ba năm cuối cuộc đời Đức Phật

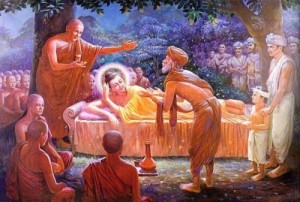

Mốc X : Đức Phật nhập niết bàn

Mốc X : Đức Phật nhập niết bàn